Our theme for this episode is the con movie. There’s no reason, topical or otherwise, for us doing this theme now, other than that “this is what we fancied doing this month”. So we picked six films from the genre, watched them, and now we’ll talk about them and tell you what we thought. No mis-directions, ulterior motives or crafty scams from us here. Well, not this time, anyway.

We’re generally not too careful about spoilers on this podcast as the films we talk about usually aren’t recent releases, but I think for this episode it’s worth sounding a general, all-episode spoiler warning due to the fact that the plot, and plot twists, are very much the point of most of these films, and we’re unlikely to be able to avoid talking about them. You have been advised. And now, join us and become informed.

Download on Spreaker | Subscribe on iTunes | Subscribe via feed

Il bidone, The Drum, or The Swindle as it’s most commonly known to those outside of the Roman Empire, is a relatively early outing in the directorial career of one Federico Fellini, in which we follow a gang of swindlers, the eldest, Broderick Crawford’s Augusto Rocco in particular, as they go about their lives of larceny. Also featured are Richard Basehart’s Carlo aka Picasso, and Franco Fabrizi’s Roberto Giorgio, surely the most Italian name possible.

Rocco’s current wheeze is dressing up like some high ranking church dude or other, and spinning a tale to remote farmers of a confession leading them to the buried treasure of a neerdowell’s stash, and that perhaps his “con-padres” could go and search for it, the church having no interest of course in the contents of the box of gold, just a small tithe of all the cash you have to ensure the heavenly accounting is in order. Or something like that, I don’t know the proper terms of this looney cult stuff. At any rate, they are making poor people poorer, and themselves briefly richer up until they spend it all on booze and floozies.

And so it goes, although Picasso has enough shame to quit the game once his wife finds out that he’s not the travelling salesman he claimed to be, and a chance meeting with Rocco’s estranged daughter seems to be threatening a similar crisis of conscience, but before that can fully percolate he’s recognised, arrested and jailed, only to be later released to get up to more desperate versions of his crimes, and, well, it does not end well for Rocco.

To my great shame I don’t know Fellini’s work well enough to tell you how this sits in his body of work, but I can at least tell you that in the context of this podcast it’s a bit of an outlier inasmuch as it’s primarily a character piece. Not to say that the characters aren’t important in the rest of the films we will talk about, but the main narrative propulsive driver in the others is the sting itself. That’s not the case in Il bidone, which is more concerned with the psychology and relationships of the con artists themselves, particularly Rocco.

It’s also an outlier in the sense that in this kind of thing, broadly speaking, the general way an audience makes its peace with being asked to care about swindlers is by having them swindle even bidder swindlers. In what’s maybe the exact opposite of what Fellini has become known for, this shows us grubby criminals swindling vulnerable, desperately poor people out of what little they have, in ways that seem all too realistic as opposed to the high concepts glossiness of the modern con films.

It more or less pulls it off, sometimes in spite of itself. Enough of the criminal gang show at least some sense of remorse or at least culpability in their actions throughout the piece to just about avoid this feeling completely repulsive, but there’s no getting around Rocco being ultimately irredeemable, which I might have forgiven if there was a deeper dive into his character or his history, in short, if in this character piece we got some real sense of his character, but I don’t think we do. Or at least, not quite enough to be satisfying. Broderick Crawford is not being helped by the dubbing, of course, but I’m left feeling his character is just not interesting enough to warrant 100 odd minutes of celluloid.

If you can deal with the moral repugnance of most of what’s going on here, there’s a very watchable film in here but it’s not exactly fun, in the way that a lot of the other films we’ll talk about here, and if you really want a proper character study of criminality I’m sure there are better options around, so I’m not giving this a full throated recommendation, but neither would I steer you away from it, but it’s certainly no undiscovered Fellini masterpiece or anything like that.

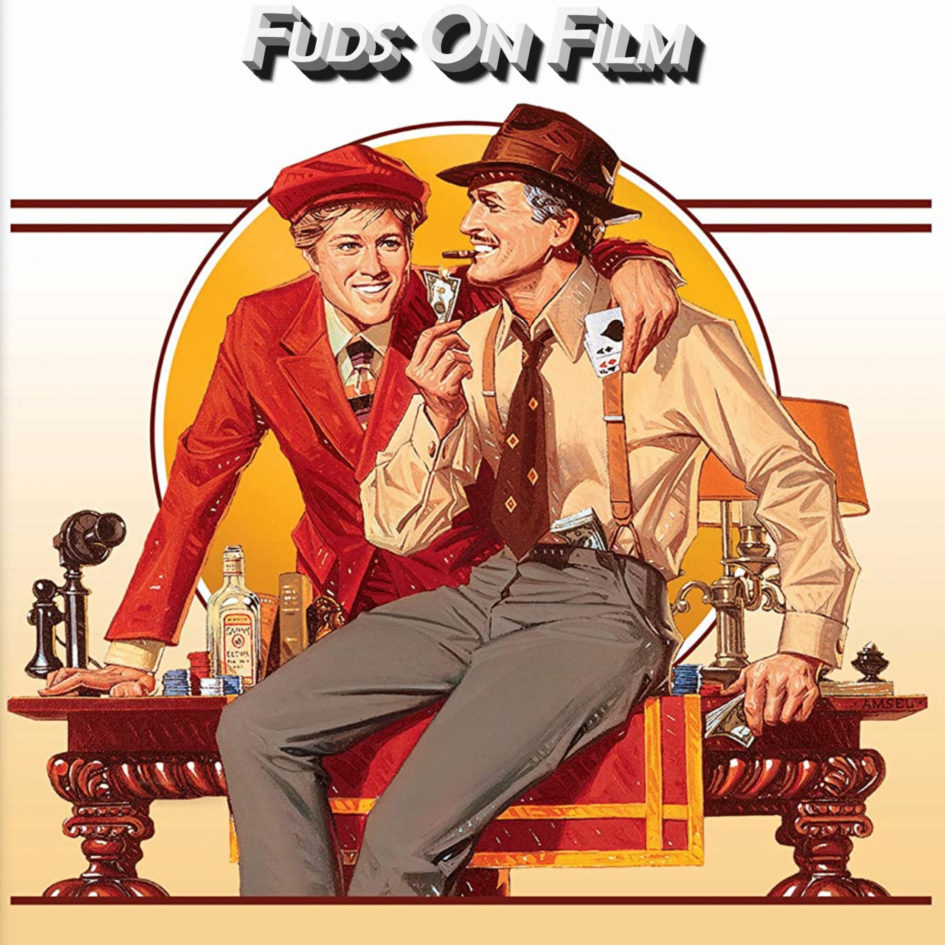

Here we have what is, arguably, THE con movie, George Roy Hill’s The Sting, from 1973, a huge hit that influenced so much of the genre in the following decades. Reuniting the director with both Paul Newman and Robert Redford a few years after their very successful partnership in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, it is the tale of a “young” grifter, Redford’s Johnny Hooker (look, I know I go on about this, but casting a nearly 40-year-old Redford in a role in which he is supposed to be a naïve young hustler, and is regularly referred to as “kid” is, frankly, taking the piss), whose partner and mentor, Luther (Robert Earl Jones) is killed after the two rob from the wrong guy.

Hooker himself barely escapes, and soon learns that his and Luther’s mark was a numbers runner for Robert Shaw’s Doyle Lonnegan, a New York crime boss and one vindictive son of a bitch. Vowing revenge, Hooker seeks out an old friend of Luther’s, Newman’s Henry Gondorff, who agrees to help the younger man take Lonnegan for a very large sum of money.

Manpower won’t be a problem, with Shaw commenting that, “after what happened to Luther, I don’t think I can get more than two, three hundred guys”, and once the con is decided upon – a setup known as “The Wire”, in which bets are placed on horse races whose results are already known due to a small, artificial delay in transmitting that information – all that remains is to hook the normally careful Lonnegan. This is done by engineering him losing a large sum of money to Gondorff in a card game, then having Hooker pretend to be Gondorff’s ambitious employee, telling the gangster how his boss cheated him. Hooker persuades a furious Lonnegan not to simply kill Gondorff, but to help Hooker take him for millions, and grab his business while they’re at it.

Bait taken, a fake betting shop is quickly put together, and Hooker and Gondorff’s plan to exact revenge for Luther in the only way they can – financially – gathers steam. It doesn’t all go smoothly, of course, with a number of problems cropping up along the way, including Lonnegan’s suspicions and unpredictability; interest from Charles Durning’s crooked cop, Snyder, and Dana Elcar’s FBI Agent Polk; and the small matter of the assassin still on Hooker’s trail over the matter of the swindled numbers runner (Lonnegan being unaware that Hooker is the same man he ordered killed), and it’s pulling surprises all the way to the end.

The Sting looks great, sounds great, is funny, smart, extremely well-acted (particularly Redford and Newman, who have a great chemistry and do a lot just with looks) and is not just entertaining, it’s FUN, with capital letters, and has been one of my favourite films since I was a child.

The action is accompanied by a superb score, a combination of Marvin Hamlisch compositions and his adaptations of several Scott Joplin ragtime pieces, most notably “The Entertainer”, which help lend the film a distinctive, jaunty and fun atmosphere. (On a side note, I just recently saw several criticisms, some contemporaneous with the film’s release, some more recent, that the Scott Joplin music was anachronistic, as if that is any sort of valid concern. I wonder if the same reviewers had a problem with Mozart’s music being used in My Left Foot, or Eyes Wide Shut or Alien or, indeed, any film ever, as Mozart died in 1791.)

Any criticisms I have are very minor – the framing of the action with the sections of the sting like acts of a play, and a list of “The Players” at the start, doesn’t necessarily detract but I don’t think adds much either, and may be a little arch or self-referential, and… no, that’s about it. Well, apart from my aforementioned issue with Redford’s character’s age, something which would only have needed a few tweaked lines to resolve. Otherwise, excellently entertaining.

I think I first stumbled across The Spanish Prisoner less because it’s a David Mamet film and more as part of a search to find something that Steve Martin isn’t unwatchably awful in. It turns out, unbelievable as it may seem, that there’s at least two such films. But that’s a different episode.

Campbell Scott’s engineer Joe Ross is whisked away to the exotic island of Val Verde to meet with his corporate high muckety-mucks about the potentially incredible value of the process he has just finalised. I believe it was the process for refining McGuffinium to Unobtainium, and we can all imagine how profitable that would be. He’s here with his day-to-day co-workers, Ricky Jay’s company lawyer George Lang and Rebecca Pidgeon’s secretary Susan, who seems quite taken with Joe.

While there, he meets and befriends Steve Martin’s wealthy stranger Julian “Jimmy” Dell, who he comes to trust so much that when Dell asks him to carry a package back to his sister in New York he agrees without even questioning what the contents are. Still, Susan’s prompting sees him open it to find out that Dell apparently on the up and up, and serious about introducing him to her sister.

This friendship would appear to come into its own when the company appears to be positioning themselves to screw Joe out of any bonus or cut in the proceeds of the process, so Joe asks for Dell’s advice, which is of course just another domino in a chain started long ago. Now, I don’t think anyone is best served by a blow by blow plot recap from this point on – Wikipedia is over there if you need it – other than to say Joe does indeed lose the process and his attempts to regain it, and escape from the frame job he’s been put in will see him in ever increasing danger as he runs out of people to trust.

I first watched this a long time ago, maybe even before seeing Glengarry Glen Ross, so the Mametian dialogue was something of a revelation at the time. It’s less so now, of course – Glengarry is where that style of speech worked as a chorus, here it’s a couple of good verses (Martin, Scott) with occasional off-key screeching (Rebecca Pidgeon). Still if you like this sort of thing, this is the sort of thing you’ll like, and thankfully I am a fan of Mamet’s affectations, although it won’t change anyone’s mind if they’re not so fond of it.

I’ve also now rewatched this enough over my long decades and decades on this accursed planet that it’s certainly past the point of diminishing returns and into actively hurting it territory, so I’m not sure how I’d react if watching this cold. Certainly my first viewing was enhanced by not having quite the level of cynicism I do now when approaching movies like this, and I’d perhaps have been less impressed with the plot if I’d applied my now standard operating protocol of “assume everyone is not who they claim to be”. That would certainly throw into rather starker relief the failure points of this multilayered con, which is altogether too fragile to exist outside of a cinema. But that’s rather the case with a lot of the genre, I suppose.

Even so, I still like Campbell Scott’s performance, and indeed still wonder why he never had quite the break I feel he deserved in his career, and Steve Martin still manages to surprise me to this day by not being awful here. In fact, he’s quite good. Turns out it’s just that comedy stuff he can’t do without making my teeth grind into a fine powder. I think, despite my earlier protestations, that on a first view there’s enough densely layered, ultimately silly cons and twists going on to keep this entertaining, so I’m still going to recommend this, albeit not as vociferously as I might have done had you asked me something back in the nineties.

We head south, now, to Buenos Aires and the Argentinian film Nueve reinas, or Nine Queens, in which Ricardo Darín plays scuzzy conman, Marcos.

While in a petrol station one day, Marcos observes young grifter, Juan, (Gastón Pauls, or “Argentinian Billy Boyd”) get greedy and try to run a hustle a second time in succession. He is found out by the staff, and Marcos decides on the spot to pose as a police officer, pretending to arrest Juan to get him away from the scene.

Marcos is not being altruistic, of course – his usual partner is out of town, and grifting is easier with someone else, and he persuades Juan to join forces with him for the day. During the course of the day, Marcos teaches Juan a few tricks, and Juan displays his own ability, while the two also learn some other, more personal, things about each other: Juan’s dad is in prison, and he is trying to raise money to bribe a judge to get him out, and Marcos is in a state of permanent war with his sister, Valeria, who hates him and believes he has stolen her, and their younger brother, Fede’s, inheritance.

Juan and Marcos’s paths cross that of Valeria that day because she calls Marcos to the hotel where she works to ask him to deal with a customer, a former associate of Marcos’s who took ill, and started calling Marcos’s name when he recognised Valeria. This associate, Sandler, was trying to reach Vidal Gandolfo, a rich Spanish businessman staying at the hotel. Gandolfo is a philatelist, and Sandler, a forger, happens to have an extremely good copy of a sheet of very rare, very valuable Weimar Republic stamps known as “The Nine Queens”.

The stamps are good enough to pass an initial inspection, but they wouldn’t stand up to laboratory testing. Gandolfo, though, is being deported to Venezuela the next day for tax irregularities, without time for such tests, so if the deal can be done today, they’re quids in. Marcos strikes a tough bargain with Sandler, and takes the stamps. After their first meeting with Gandolfo, though, the stamps are stolen by thieves on a motorbike, then unwittingly discarded, leaving Marcos and Juan to come up with a con on short notice to acquire the genuine stamps and still turn a profit.

Is it possible, though, that this seeming short con is, in fact, part of a much larger, long con, and that the mark is not who we first believe? Well, yes, obviously, otherwise I wouldn’t be asking that question. But the fun comes from the discovery of that, and the motivations for it, with everything explained succinctly, and not excessively, in a low-key final scene that I really appreciate.

I find Nueve reinas a very well-crafted and well-acted film (especially Ricardo Darín, who I’m a huge admirer of), with satisfying twists and turns, and a strong, funny script from writer-director Fabián Bielinsky, considerably better than anything David Mamet achieved in this genre.

I really recommend Nueve reinas, and I doubt many English speakers will have seen it before. You may, however, be familiar with 2004’s Criminal, starring John C. Reilly, Diego Luna, Maggie Gyllenhaal and Peter Mullan, which is the same film, more or less, but mostly less. Out of interest, I watched Criminal today before we started recording, and it’s nearly a scene for scene remake, and pretty close to a line for line remake, too. Even allowing for knowing how the plot progresses, it’s a substantially worse film, especially in the acting, which was quite a surprise, and in the few places where it deviates from Fabián Bielinsky’s original it is materially worse. So avoid the remake, and watch the real deal instead.

My knowledge, memory and expectations of Confidence heading into this episode were best characterised by the numeral zero, although a quick glance at IMDB and seeing James Foley directing, he of Glengarry Glen Ross fame certainly raised some hope, balanced only by Doug Jung’s shared writing credit on The Cloverfield Paradox. Which way’s this going to fall?

Edward Burns’ Jake Vig and his gang of ne’er-do-wells have just finished conning some mark out of a stack of cash, which will soon have lasting consequences when they find out that mark was working for a local crime lord, Dustin Hoffman’s Winston “The” King. Jake is encouraged to proactively make amends after one of his gang is found killed, and meets with King to come to an arrangement. They plan to con a large sum of money from one of King’s rivals, Robert Forster’s Morgan Price, who happens to own a bank.

King agrees, but insists that his goon, Franky G’s Lupus string along with his usual gang of Paul Giamatti’s Gordo and Brian Van Holt’s Miles, also recruiting Rachel Weisz’ Lily to help with a plan to befriend and bamboozle bank VP Leon Ashby, played by the dependable John Carroll Lynch. Getting in the way of things are the gang’s semi tame bribed cops played by Luis Guzmán and Donal Logue, who are being blackmailed into, well, doing their jobs by Andy García’s Special Agent Gunther Butan, who’s been on the trail of Vig for many years and sees this as a prime opportunity to take him down.

And, I suppose that’s all the set up you need, and by this point in the episode I don’t think you’ll be too surprised to find out that things are not what they seem and perhaps you can’t trust anyone involved in any aspect of this film. Or most of today’s films for that matter, but this one in particular has a highly unreliable narrator, which is perhaps the closest this film came to displeasing me.

The rest of it is glossy and slick enough that any emotion refuses to adhere to it, be that positive or negative. It’s pacy enough that it’s never boring, and it’s a very easy, fairly enjoyable watch, but it’s not a film that’s going to make any kind of impact, apart from one day in the future wondering why it doesn’t show up on Ben Affleck’s IMDB page, before remembering that it did in fact instead star the discount, Poundland Ben Affleck, Edward Burns.

If I was in a worse mood I would perhaps be meaner about a film that gathers this amount of talent together without giving any of them anything particularly remarkable to do, but I suppose that also means no-one’s particularly bad. I can’t think of a lot else to say about Confidence other than to reiterate that it’s an very enjoyable watch that I’ve already largely forgotten, so it’s a good piece of disposable entertainment which makes it easy to recommend that you rent rather than buy.

The con movie is quite a popular genre, and there were quite a few films we could have selected for this episode. Some of the discarded options were the curiously popular A Fish Called Wanda, which, after recently re-watching, I can confirm is very much the terrible film I thought it to be; The Prestige, which is excellent but one we’ve covered before; Dirty Rotten Scoundrels, which is fine but Steve Martin’s gurning makes me want to claw my eyes out, though clawing his out seems fairer; and The Good Liar, a con-cum-revenge thriller starring Helen Mirren and Ian McKellen, that doesn’t quite stick its landing but is quite interesting.

No, instead, we chose to finish with a film in which Mark Ruffalo is the mastermind of many elaborate cons, and which features magic tricks and exotic locations. No, not Now You See Me. Obviously not Now You See Me, because Now You See Me is insultingly stupid, nonsensical trash of the lowest order and, more pertinently, we, collectively, are offended to our very souls that the sequel to Now You See Me is called Now You See Me 2, and not Now You Don’t. It was right there!

What we selected instead is 2008’s The Brothers Bloom.

So, here’s a rather odd take on the genre: con movie as romantic comedy. A romantic con-medy, if you will. And being both written and directed by Rian Johnson, you know that it’s about family, and that’s what’s so powerful about it…

Narrated by Ricky Jay (yes, him again – I mean, I liked Ricky Jay, but other magicians are available), The Brothers Bloom tells the story of two brothers, Stephen and Bloom (possibly making the latter’s name Bloom Bloom, which just makes me think of Basil Brush), played by, respectively, Mark Ruffalo and Adrien Brody.

During a troubled youth, in which the siblings were kicked out of a succession of multiple foster homes (reasons for this including “sold our furniture”, “molested cat” and “larceny”), Stephen writes his first con a way to get Bloom to talk to a girl, and has an epiphany, and finds his calling: writing and creating elaborate cons and bringing them to fruition, changing reality to match his narrative. Though successful, the adult Bloom is tired, after a quarter of a century, of feeling like nothing more than an actor in Stephen’s plays, and desires something real. He thus leaves Stephen in pursuit of some reality.

Three months later, Stephen finds Bloom in Montenegro, enjoying whatever reality the bottom of a bottle offers, and persuades him to return to their little outfit for one last con. The mark this time is Rachel Weisz’s Penelope, a reclusive polymath and heir to a substantial fortune, and whose trust it is Bloom’s job to earn. Once hooked, Penelope joins Stephen, Bloom and their silent partner, Bang Bang (Rinko Kikuchi), aboard a steamer bound for Greece, from whence, with Penelope under the illusion that she has joined a gang of smugglers, they head for Prague, Mexico and St. Petersburg. And much of what happens along the way – and I ask you to steady yourself for a shocking revelation here – may not be what it seems! And Bloom falling in love with Penelope is absolutely not part of Stephen’s masterplan, in which he tries to reshape the world and create endings. No.

Like The Sting, the onscreen titles for the different sections are unnecessary, though here may be more acceptable and legitimate, due to the film’s meta-narrative narrative, and indeed may well be a direct reference to The Sting. The Brothers Bloom is in many ways a story about stories, and has been criticised for being too pleased with itself and its many literary references, and for being, to use the word a second time in this episode, too arch. And I can see where such criticisms are coming from, but I don’t share them, I just had a hell of a time with this film and enjoyed it thoroughly.

It’s beautiful, funny, smart and twisty (though what the big twist was going to be I was never in doubt, particularly due to a line delivered in the first half of the film by Ruffalo that had about a hundred lanterns hanging on it, it was the when and how that kept me guessing), and its central pairing is excellent, with Adrien Brody in particular capable of a really nice mix of comedy and pathos. Rachel Weisz adds a lively optimism to the group dynamic, and Rinko Kikuchi’s wordless role provides not just humour and interest but helps stop this being a total sausage fest, largely setting it apart from everything else in this episode.

The Brothers Bloom also has the second and third best comedy implementations of a Lamborghini after The Wolf of Wall Street, and while that wasn’t a mental list I was keeping, it certainly is now.

Thanks to everyone who has got in touch with us on this, or said kind words about the show – it’s all very much appreciated.

If you’ve been affected by any of the issues discussed today, please hit us up on Twitter (@fudsonfilm), on Facebook (facebook.com/fudsonfilm), or email us at podcast@fudsonfilm.com. If you want to receive our podcast on a regular basis, please add our feed to your podcasting software of choice, or subscribe on iTunes. If you could see your way clear to leaving a review on iTunes, we’d be eternally grateful, but we won’t blame you if you don’t. We’ll be back with you soon with something fresh, but until then, take care of yourself, and each other.

Leave a Reply